As part of Whitman-Walker’s 40th anniversary, officially January 13, 2018, we’re sharing 40 stories to help tell the narrative of the Whitman-Walker community.

As we approach the end of 40 Stories for 40 Years, listen as members of the Whitman-Walker community reflect on what years of service to Whitman-Walker and the fight against HIV taught them, what they wish they knew then, and what they hope for the future.

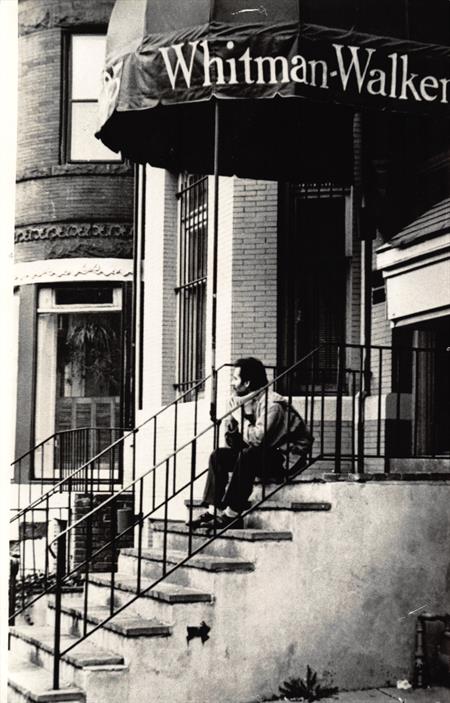

Gene Frey, namesake of Whitman-Walker’s volunteer award, sits on the steps at the Clinic’s 18th Street location in Adams Morgan.

What did you wish you knew when you first heard of HIV?

D. Magrini – a Whitman-Walker employee and former Bill Austin Day Treatment Center volunteer:

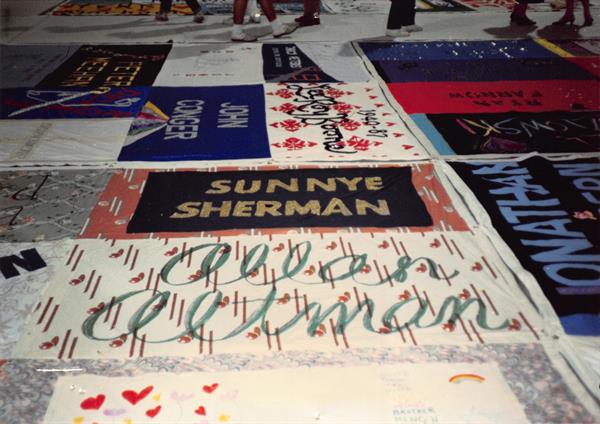

“Oh, I wish they had told me they made a giant-ass mistake. I wish – I wish they had told me they made a giant-ass mistake. I wish they had told me what it would look like to have – what in my heart were my three kids and my wife – all on the National Mall with the whole shit laid out, with it laid out and it went as far as you could see. As far as you could see, and having one of my kids look down at one of the panels – and I know she didn’t understand what this meant, but it said, ‘I love you, Daddy,’ and it was like, a leather – a leather homage to somebody’s Leather Daddy but my kid saw ‘Daddy’ and broke. Her little body just went [cracking sound]. They knew my friends; they knew people that were sick, that were – I wish somebody had been able to tell me to be ready for that. To be ready to find my friend in the house with his tee shirt on that he’d had on for two or three days and all he wanted to do was be able to get up and cross the room and he couldn’t do that anymore.

I wish somebody had been able to tell me how – what it looks like and what you hear with somebody telling you they’re going to die. That’s what they believed, and they told you, and to have them turn around from the phone call, tell you, and then watch the back of their head just – they turn around, and you’re watching that. I wish somebody had been able to tell me those things. I wouldn’t even want them to tell me about where we are now. And where we are now – where we are now is only where we are now, and I don’t know for how long, in pockets. Because the shit as I remember it 20 years ago in this city, I could probably walk to a pocket of this city where this shit looks exactly the same as it did and if it’s not in this city, it’s in some reachable area. Somewhere in Baltimore, somewhere in Virginia.

All of this good news I got, it ain’t – it’s like watching crack and the opiate epidemic. Crack was: ‘Crack addicts, you goddamn bastards.’ Opiates: ‘Oh, my dear God. We’ve got to get some shit over here. People are on opiates!’ Some people seem to be worthy of saving and some people are just going to be waiting. They’re still waiting.”

A photo of a portion of the Names Project – AIDS Memorial Quilt dedicated to Sunnye Sherman, the first woman to go public about her AIDS diagnosis in the nation. She passed away shortly after Whitman-Walker names their AIDS Education department in her honor.

Amelie Zurn – the first Lesbian Services Program director:

“Hmm. Well, I think many people naïvely thought, ‘This is a virus. We’ll find a cure. This is, you know.’ Before we even knew it was a virus, this is, ‘We’re going to find a cure. This will be done in a little while.’ I think the unique way that it brought up sexuality and sort of all of the intersections of oppression, you know, it’s just kind of like, ‘Hang in there. This is going to be around, and we’re going to see this play out the way that many other epidemics play themselves out.’ But also, that naïvely wonderful sense that we could make a difference is kind of incredible too. So, I don’t know, I mean I guess people would have just said, ‘Hang in there.’ Which I knew I already had to hang in there, but so, I think there was a lot of optimism for me that getting into HIV/AIDS that people would feel more comfortable and more connected to their bodies and could really work towards creating lives that they felt in control of and empowered around. I think that was always my hope, and I think that’s true for some people and some people not. I mean, I think, I know we still have so much work to do.”

Randy Pumphrey – a Whitman-Walker employee and former chaplain at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in DC during the AIDS epidemic:

“So, this is a – this is a weird story, kind of voodoo. So, during those – it was right after Bruce had died, probably about six months after Bruce had died and my friend Jan Sheryl, who is a poet from Baltimore, [Maryland], gave me a gift to go see this psychic tarot card reader in Baltimore City that he had met. So, I went to see her and you know, she gave me the cards and she told me to hold them and shuffle them and think about them, and then she brought me into the room and she explained what she does and she said – she took the cards and she said – she said there’s a spirit that kind of tells – she had this spiritual person who would tell her things in the session. She said, ‘Oh, you’ve brought somebody as well here,’ and I said, ‘Well, my friend Jan is down in the shop. He gave me this gift,’ and she said, ‘No, he’s in the room,’ and she said, ‘He’s a young man, probably like 27. He’s got a very sarcastic sense of humor and he’s telling me that you helped him die.’ And I went, ‘Bruce?’ and I started welling up, and she said, ‘He says yes, it’s him. It’s Bruce.’ And she said, ‘He wants to sit in on this reading because he has things that you need to know,’ and I said, ‘Okay.’ So, he’s – she said, ‘He wants you to know that in your life you’re going to witness something really amazing. That you’re going to see it. It’s going to be really amazing, what’s going to happen, and you’re going to see it. And you’ll know it when you see it, and I’m so happy you’re going to and thank you for helping me, because where I am is terrific.’

And I think today, in 2018, I go, you know, ‘Will there be a time when we don’t have HIV? Will there be a time when we’ve just rendered this thing helpless, that we can just block it or stop it?’ and I already see that. I see people living and thriving and I see people still committed to research and trying to figure out the next steps. And I think this is what he was talking about; that I would have the opportunity not to just be in – because those were still in the days when everybody was dying when I did that reading and I literally did not think that the war, that death event, would ever end. It was just like one big death event. But I’m not in that anymore. I did survive, and I do see a different world. And now, I see a world that’s even bigger with the LGBTQ issues. You know, I see the stuff that we do here around trans health and gender-affirming care and I see the, you know, the challenges of all the boundaries within the LGBTQ community and I see that – you know, it’s kind of like what I said before. You know, you think the boundary is there and the boundary isn’t there. The boundary is farther out and there’s much more to learn, much more to explore, and I think of all the amazing young people who are – who are teaching still. So, I think of myself as being, you know, Harold Beck or Joe Weber saying, ‘You have something to teach me. I need you to show me, because I don’t know this. There’s territory for me to explore and you’ll show me. You will show us. You will show this health organization, and we will keep going and we will be better.’”

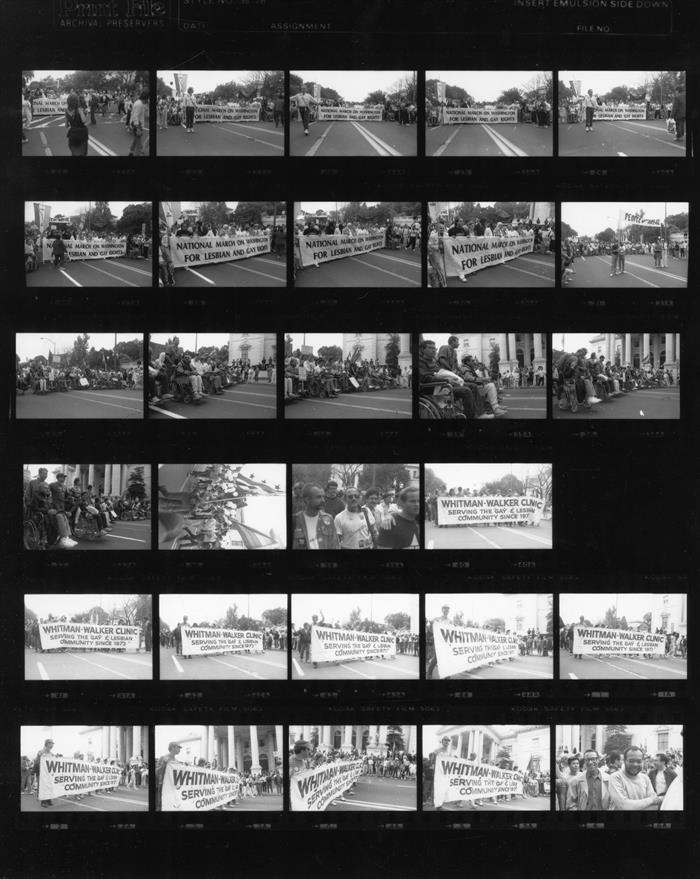

A photo of the “People with AIDS-ARC” contingent at the 1987 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

What do you hope for Whitman-Walker’s future?

Randy Pumphrey – a Whitman-Walker employee and former chaplain at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in DC during the AIDS epidemic:

“I think what I want to see is we continue to be as progressive as we can without losing sight of the persons who are long-term survivors. I get worried sometimes that the focus is only on those who are just getting infected or – or what’s happening right now instead of – and losing sight of the person who is now aging in HIV. And I think that we have really tried to do that where there’s been some emphasis on trying to understand how we provide elder care for persons with HIV, but also our real initiative into youth, because I’d like – I’d like – it’d be cool to know that – and we’re already doing it where the kids are educated about risks and non-risks and how to take care of themselves and how to have sexual health and

how to feel good about themselves and how to have esteem when they’re young so they don’t have to grow – they don’t have to do it when they’re 30 and 40; that they’re figuring it out earlier. I also – I also think that we have the opportunity in a new way with the spiritual community to – to integrate. I think that there – there have been those partnerings, but I do think that – it used to be there was a time in my early life thatI was – you know, as a spiritual person within the gay community I was seen as an anomaly. I was not the norm, and so some people really distanced themselves from me. Now, I see that that doesn’t have to be the case and this is the plurality of spiritual/religious traditions and the acceptability of the LGBTQ experience within those traditions and how Whitman-Walker can also play an important role in continuing that conversation and developing those partnerships. And I think especially as we think about broadening our reach over in the southeast [Washington, D.C.] – and I understand that that community is a very fast-changing community, but still, you know, especially in the African American community and the African American church or in other conservative traditions like Islam. Working with imams and working with communities to make sure that the message of inclusivity and awareness and education is there, because we’re at a time when that can happen in a way that could never happen before.”

Tony Burns – a former member of the Bill Austin Day Treatment Center program and current Lead Peer Mentor at Whitman-Walker:

“Whitman-Walker is a godsend. A lot of people there know me. They know I’m a straight shooter. I was also the coordinator for their Patient Advisory Council. They no longer have that. They just ended it last year. I think that should be re-visited. I’ve done all different modes of media for them: print, TV, video. This building [WeWork at 1342 Florida Avenue NW] that I did not come to until a few months ago has a picture of me on the front of the building. I love them. They helped save my life, no doubt about it. Things that I’m—could change? I think there needs to be more diversity in the staff. For instance, we need to see some more black doctors, some more black health care professionals. Why? Because D.C. has a majority of African Americans. D.C. has a high LGBTQ black population, and we need to come into a place and see that there are professionals who look like us. That can’t be understated. It’s not overrated. It’s a reality, and I am vocal about it. We just don’t need to see people in here, their stories. We need to also hear from the black doctors, the black health care professionals. We also need to see more success stories about them taking people from the lower rungs and investing in those people and growing those people; because those people can reach their peers and folk of their culture in a way that is needed.”

Ellen Kahn – a former Lesbian Services Program director:

“Yeah. Well, I’m super proud of Whitman-Walker. I mean, you know, I did have a little skepticism initially when they were going in a new direction. I thought, ‘Oh, I mean, is it going to lose it’s LGBTQ identity? Is it going to, you know, still be a place where people like me feel comfortable going?’ And you know, I think that there was a – the question was really legit for a while. Now, 13 years since I left, I have no doubt that they are committed to and very focused on being the premier health center for the LGBTQ community. I chose them as my primary care provider in my CareFirst HMO, proud to say. I was actually very happy to know that right around the time One Medical decided to no longer accept CareFirst HMO that Don and the team at Whitman-Walker immediately knew that was a need and an opportunity. A lot of trans folks were getting their care at One Medical; a lot of queer folks like me, and they really pushed and very quickly were able to get into that program. So, now I can get my care from Tina [Celenza] or Barb [Lewis]. And so, what I hope is to see them continue to, you know, be accessible and responsive to the diverse LGBTQ community, to have that leadership in ending the HIV epidemic here in DC, one of the places hardest hit in the country. You know, I would personally love to see ways that Whitman-Walker could fill some of the programmatic and support gaps that still exist. I mean, it’s great to have the DC Center and a lot of other organizations. A lot of them are very socially-focused. I feel like queer people always need space to just come out, talk to peers, learn how to, you know, adapt to a new city if they’re new to the city, and I think Whitman-Walker really can be many things to many people.”

A photo contact sheet from the 1987 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.