By Benjamin Brooks & Abigail Schanfield

Using census data as well as HIV and COVID-19 epidemiological records, the authors of “White Counties Stand Apart: The Primacy of Residential Segregation in COVID-19 and HIV Diagnoses” compare the racial composition and HIV and COVID incidence rates in counties across the United States.

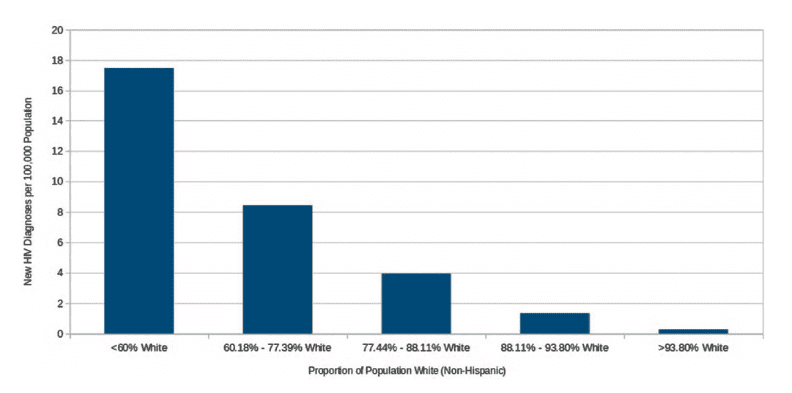

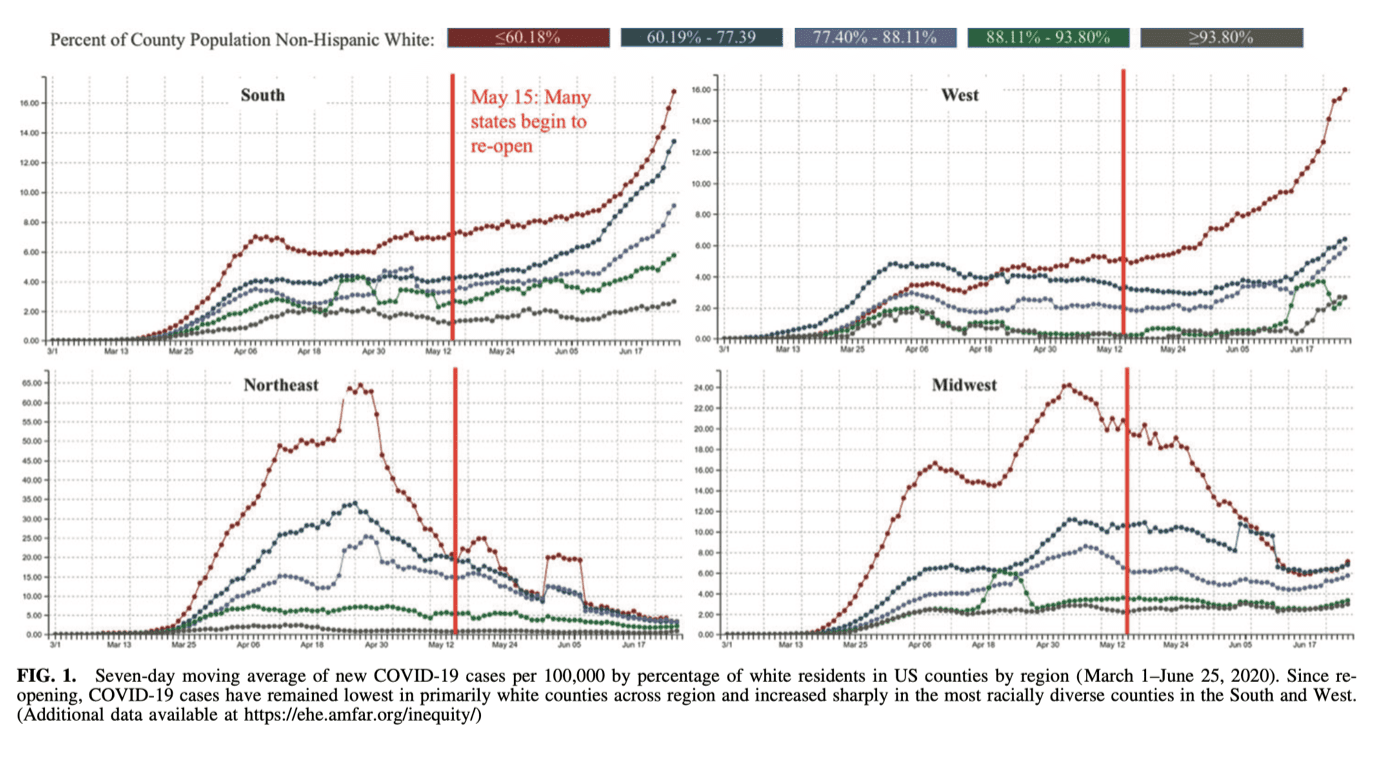

While Black Americans make up only about 13% of the United States population, counties with a higher proportion of Black Americans accounted for 47% of COVID-19 cases and 54% of deaths. Their findings show that historical racial segregation has an impact on the current health and wellbeing of America’s communities. Whether in rural or urban areas, counties with the highest percentage of white residents have the fewest cases of COVID-19 and HIV.

This insightful article, published in AIDS Patient Care and STDs, was written by a team of researchers that includes Whitman-Walker Institute Board member Greg Millett. The study shows racial disparities persist across the United States: the differences in HIV and COVID infection rates between majority white and racially diverse communities can be seen in the North and South, East and West of the country.

These inequities in infection and death rates are rooted in structural inequalities that can be traced to racial discrimination. The study describes the connection between the history of redlining—a structural form of racial segregation that was legal until the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 — and these contemporary health inequities.

Other research similarly shows that housing segregation systematically disadvantages communities of color and contributes to gun violence, a lack of resources like clean air and water, healthy food, medical care, and public education, among other resources like transportation and parks & recreation.

The work ahead is to understand and eliminate health inequities. In their data the authors find a place for hope that racial inequities can be reduced. The data show that people who are active members of the U.S. Armed Services have less pronounced disparities in HIV treatment, and Black and Latine veterans did not experience excess COVID-19 deaths when compared to white veterans.

There is little doubt that dominant cultures of whiteness and masculinity continue to challenge the health of members of the U.S. Armed Services. These examples demonstrate, however, that when housing, education, nutrition, and medical care are accessible to all, as in the armed forces, many racial health disparities disappear. The research suggests that equitable investments in historically disadvantaged communities can eliminate racial health disparities.

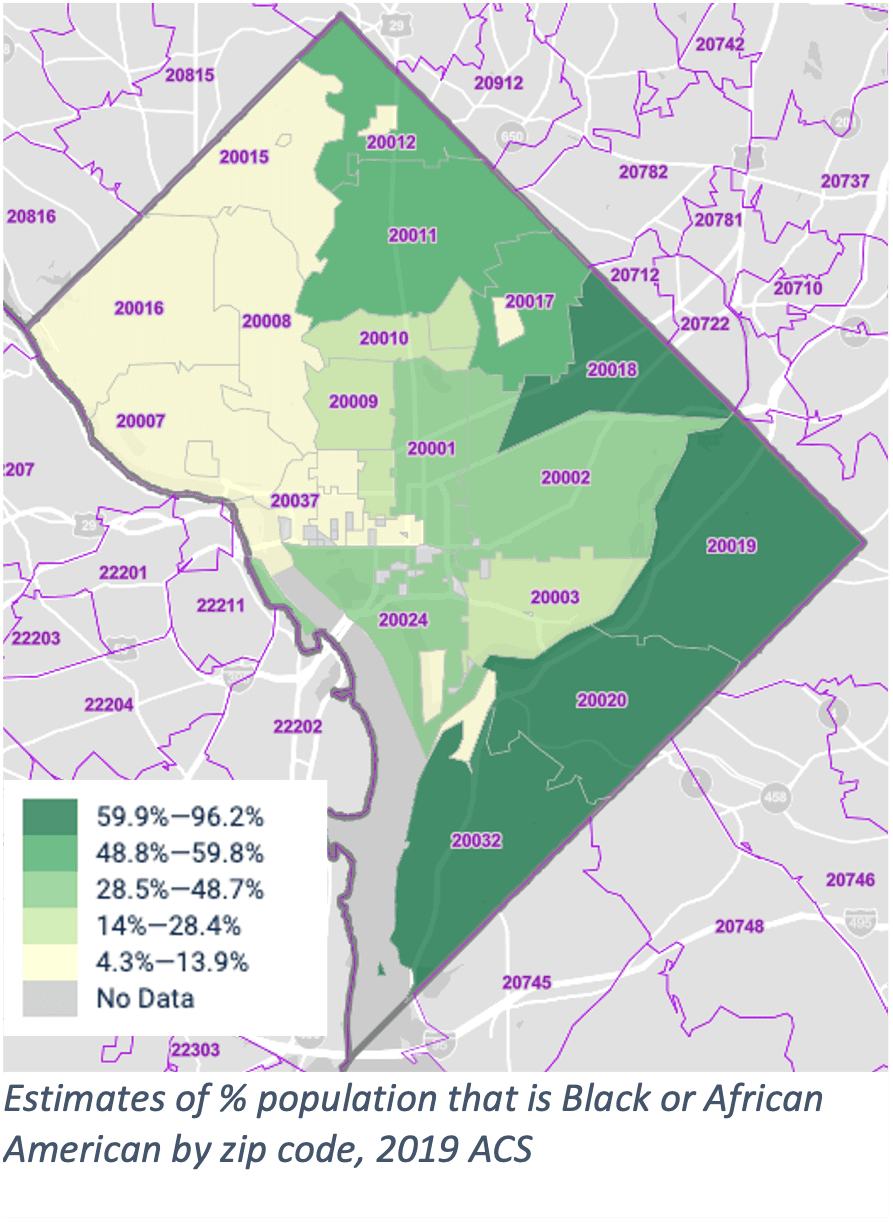

In Washington, DC, racial segregation effects the wellbeing of DC residents, as investments in public resources are inequitably distributed across DC’s 8 Wards. In DC’s demographic changes over the last 40 years, we can see that, while legal mechanisms that support racial segregation were abolished with the passage of the Civil Rights Act in the 1960s, the mechanisms of white flight, gentrification, and anti-Black racism continue to exclude Black people from many spaces and restrict the availability of resources for historically Black communities.

Markedly, access to resources like supermarkets, schools, parks and recreation facilities, public transportation, and medical centers is more difficult in the majority-Black Wards 7 & 8 than the wards on the other side of the Anacostia River. This inequitable access drives the racial disparities in COVID-19 and HIV outcomes that persist in DC, along with disparities in other health outcomes like heart disease and diabetes. The current challenge is to continue to prioritize investments that improve public resources in DC’s Ward 7 & 8 communities.

Markedly, access to resources like supermarkets, schools, parks and recreation facilities, public transportation, and medical centers is more difficult in the majority-Black Wards 7 & 8 than the wards on the other side of the Anacostia River. This inequitable access drives the racial disparities in COVID-19 and HIV outcomes that persist in DC, along with disparities in other health outcomes like heart disease and diabetes. The current challenge is to continue to prioritize investments that improve public resources in DC’s Ward 7 & 8 communities.

Part of this undertaking is bringing events, parks, and community health services to the St. Elizabeths campus in DC’s historic Ward 8 community. Along with businesses and housing, the redevelopment will bring public outdoor spaces and medical care facilities to this part of the city. As a core partner in this effort, Whitman-Walker looks forward to working with residents and community leaders across the great Ward 8 to ensure that everyone has access to the resources they need to thrive in healthy neighborhoods.

To connect to health supporting services in DC, including COVID-19 vaccines, visit DC Department of Health’s Link U website. For information about Whitman-Walker’s services, visit our health center website.