As part of Whitman-Walker’s 40th anniversary, officially January 13, 2018, we’re sharing 40 stories to help tell the narrative of Whitman-Walker in community. This week meet Gerard Tyler! In 2017, Gerard hit the 15-year milestone of volunteering his time, energy and empowering authority to the Gay Men’s Health & Wellness Clinic. This is Whitman-Walker’s walk-in sexual health clinic and our longest-running program, originally started in 1973 as the Gay Men’s VD Clinic. A native Washingtonian, Gerard shares his story about growing up in DC, life at the height of the AIDS crisis, and his own experience with HIV care. Gerard continues to volunteer his time and mentorship.

Click the orange play button below to hear Gerard’s November 19, 2017 oral history – a recorded interview with an individual having personal knowledge of past events. Thank you to the DC Oral History Collaborative for supporting the collection of this oral history.

Five Quotes from Gerard’s Oral History

On Nightclubs in Washington, DC:

“A dungeon. Dark, but house music always have dark – not pitch dark, but close to it, but you know, it’s always dark, you know. I remember dancing and the floor, it must have been a tile floor, but because of all the sweat and the heat, if you wore white pants, it was very popular to wear white pants, your pants would have this mud-like on the bottom of it when you come out. I never wore a pair of white pants twice, because what, whatever it was wouldn’t come out, that’s why. But a small club, small dance floor, hot as hell. I remember just, I could just wring my shirt out, you know, but it was, but then again, I was, what 19, 20 years old, you know. So, what seemed to be annoying to me now, was not, you know.”

On Lunchtime Disco Breaks During the 70s:

“When you would go, oh, I’ll tell you about disco. I worked at the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. At lunch, there was a club, it was a straight club, down on 13th and E called The Mark IV. Mark IV, Mark V. I think Mark IV. This is how big disco was. They had noon-day disco. We would go down there at lunchtime to dance, and then go back to work. That’s how big disco was. Do you hear me? You haven’t heard of that, a club opening up for anything, you know, no. Disco was, oh, gosh, dis – you would go, and buy an outfit. You would start disco-ing actually, from Thursday until Sunday. You would drag your ass into work because you went out Thursday night, and then disco right on through Sunday, and they even had Tea Dances which started at 12 noon, and I remember going to the Tea Dance at 12 noon, Sunday, and leaving the club at 2 AM when it closed that morning, and never ever leaving the dance floor once. We’d be on the dance floor the entire time. That was with a group of friends. I don’t know, I know you’re not getting the full picture. Not only that, you would pick out your outfits. You planned what you were going to wear, you know. Yeah.”

On the First Time He Heard What Would be Known as HIV/AIDS:

“Oh, God, I’m trying to think. I want to say, and I can’t remember exactly, but I do remember it was one of the kids who worked on the corner who they were talking about had this, I can’t remember the exact word, but they were talking about HIV. At that time, it was a white man’s disease until and later it drifted in. You know, when it became, I guess, full-blown or whatever when it started invading the USA. At that time, it was called ‘GRID.’ I have to say, and I was very standoffish because you didn’t know. I was very afraid because nobody knew how you would catch it, you know? I mean just no knowledge at all. They just know people had it. It was a very bad look because I forgot what they called it when you would see the spots. You don’t see that anymore, you know, not often, you don’t see that.”

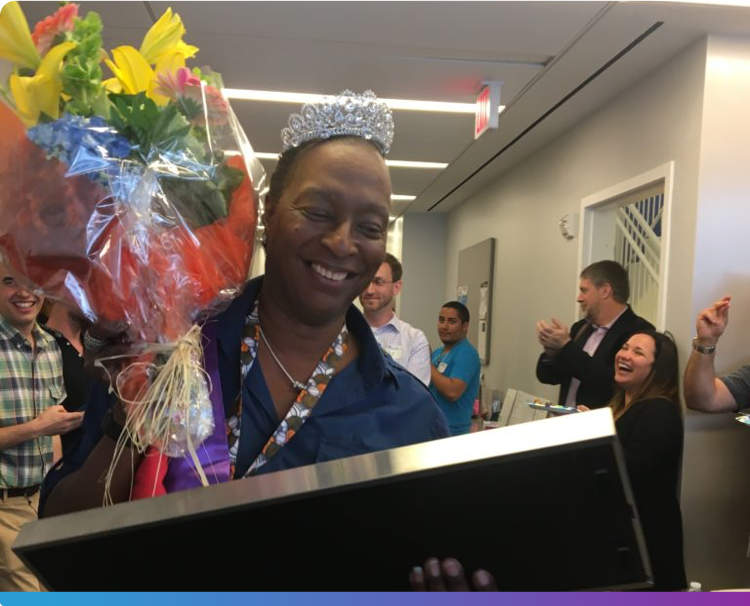

Gerard is celebrated for his 15 years of volunteer service at Whitman-Walker Health.

On HIV Entering His World and Community:

“But I wasn’t concerned with it, because like they said at that time, it was like a white man’s disease. As it progressed, and started crossing over into the Blacks and Hispanics and everything, and it started hitting my circle of friends at the club, because that I never, you know. It was a hard thing, yeah. I’ve seen the progress though from the later drugs, the antiviral drugs which help save a lot of people lives, but the one, oh, God. The worst experience – not experience, but the worst story that I ever heard that I heard this later. It was a guy who I used to date, matter of fact, Kermit [Turner], we found out years later talking that he dated this guy too, and another friend of mine. Yes, and but not at the same time, but at different times, and come to find out he had jumped out of a window when he was diagnosed and, at, at DC General … And when they gave him his diagnosis – when he was diagnosed, he jumped right out the window and killed himself. And at that time, it was a death sentence, you know. Yeah.”

On Taking Friends and Himself to Get Tested:

“No. It was right, it had to be the Austin Center where they did their testing. And she said, ‘Take me to get tested.’ And I said, ‘Okay.’ Well, I sat

in the car, and then all of a sudden something said, ‘You ought to go in and get tested.’ So, she, excuse me, she had been there for a while, and at

that time, you had to wait, like, I can’t remember now. I know it was at least a week, coulda been two weeks before your results came back, and because they didn’t have the rapid test at that time. And so, she had maybe been, I can’t remember how long, but I know she had been in the building for a while. And I sat there, and I said, ‘I’ll go in and get tested.’ And I had no reason whatsoever to get tested, or to even suspect. So, I always say if you don’t believe there’s a God, there is a God. So, I went in, got tested, but I never went back to get my results. Weeks went past, and another friend called me up, and said, ‘Gerard, would you take me down to get tested?’ And I said, ‘Sure.’

So, when that person was down there, I sat in the car, and I said, ‘Oh, you know what you got tested. Just go on in, see your result.’ That’s when I found out. So, I always said, ‘There is a God.’ Because I had no reason, hadn’t planned to go. I wasn’t going down to get tested, had no reason. I was in a monogamous, or at least I thought I was, relationship. I don’t, my outlook on it, I’ve had friends who once they found out, they started, because I found out I had a number who were HIV-positive start a high number of alcohol, drugs. I’d never drank, and I never took drugs, and I never resorted to drugs or drink to even to forget, or how to soothe the pain of having HIV. I’ve always owned it, and I always tell, because I’m in a mentoring program at Whitman-Walker as well, and my mentees, I always make them own it. You can put the blame wherever you want, but the blame lies with whom? You. You had the right choice for to use protection. You can blame the other person all you want, but ultimately, you had the choice to use protection. To me, you have to have that outlook, because you run around and you kind of put blame and this and that. It’s not helping you. You know?”

On His Work at Whitman-Walker:

“I volunteer, and I do the STD clinic, and I help everybody that I can do, but I can help. I do. That’s my sole purpose of being there.”